Let’s just get this out of the way. The first thing everyone says about neural networks is that they’re a “black box”. It’s this magical, unknowable thing that somehow “thinks.”

Frankly, that’s not a very helpful way to start. It’s also not entirely true.

We do understand, in detail, how they work. We built them. We know the math. The “black box” feeling comes from something else. Think about your own brain. You can recognize your best friend’s face in a fraction of a second, in a crowd, in bad lighting. Now, try to write down the exact rules for that.

Could you write a step-by-step program? “If pixel (3,4) is a skin tone and pixel (3,5) is dark, check for ‘eye’… ” You can’t. You don’t know the rules. You’ve “lost track of which inputs taught you what and all you’re left with is the judgments.”

A neural network is the same. It’s not magic. It’s just a system that learns like that. Its intelligence is an emergent property.

And this is why so many people get stuck. When you’re learning to code, you use tools like PyTorch and you’re told to “add a layer”. It feels like you’re just connecting Lego pieces, but you have no deep, intuitive feel for what that “Lego” is doing. You feel lost because you’re looking for explicit rules in a system that doesn’t use them.

So, let’s build that intuition. The “how it learns” is completely understandable.

The Big Idea: It’s a Factory, Not a Genius

The biggest mistake I see is thinking of a neural network as one single, brilliant brain. It’s not.

A better analogy is a factory assembly line. It’s a system designed to take a pile of raw materials (the input) and turn it into a finished product (the output), step by step.

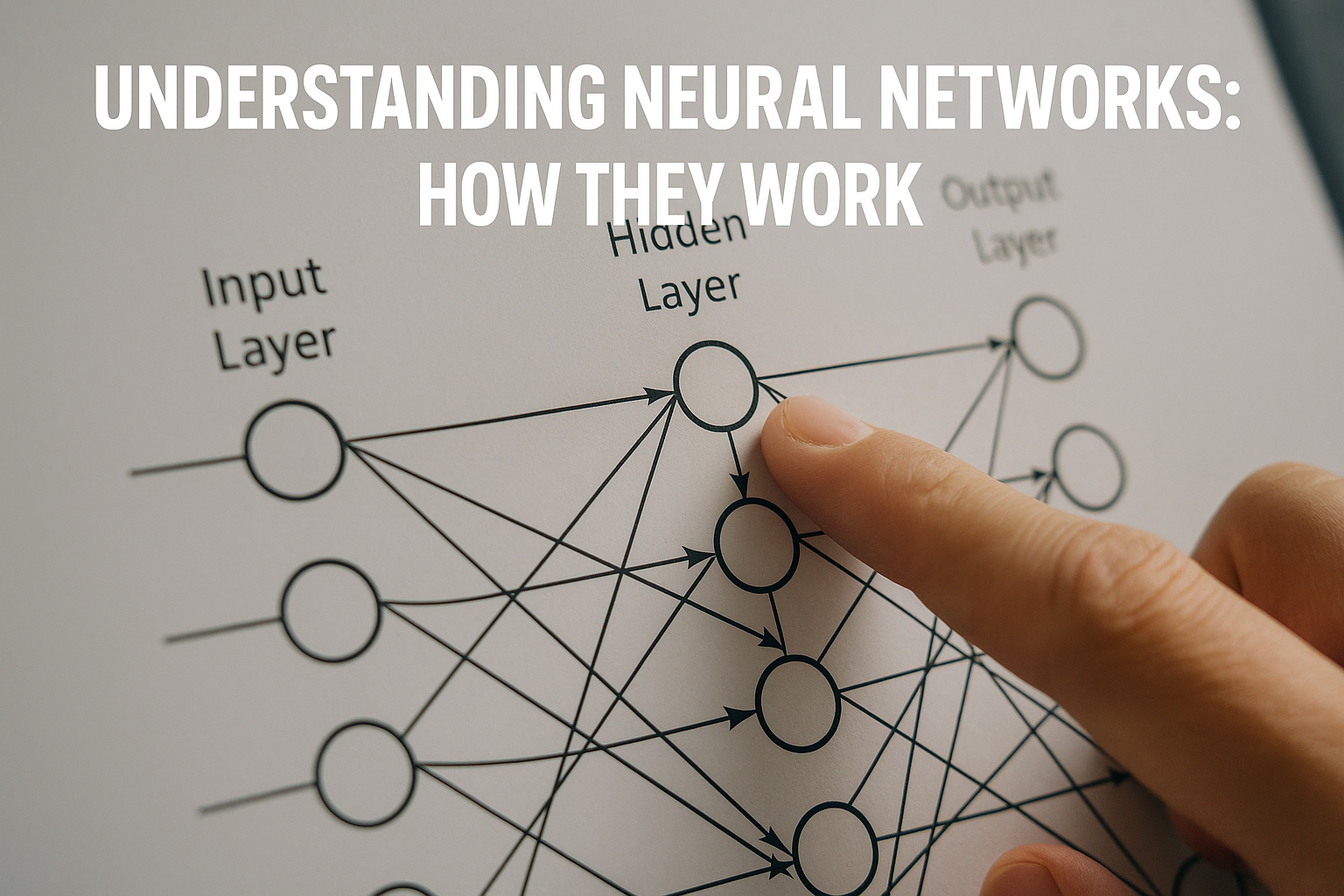

The network is made of “layers”. Think of each layer as a different station on the assembly line with its own specialized workers.

- The Input Layer: This is just the loading dock. It’s where the raw materials (your data) arrive. This could be the pixel values of an image, the words in a sentence, or the audio from a song.

- The Hidden Layers: This is the factory floor. This is where all the real work happens. It’s called “hidden” because you don’t see its work directly—you only see the raw materials that go in and the final product that comes out.

- The Output Layer: This is the shipping department. It takes the final, processed assembly from the last hidden layer and puts a label on it. “This is a ‘cat’ with 98% certainty.” “This email is ‘spam’.”

No single worker in this factory is a genius. In fact, each worker is almost laughably simple. But by arranging them in layers, where each layer adds complexity and abstraction based on the previous layer’s work, the system can perform incredibly complex tasks.

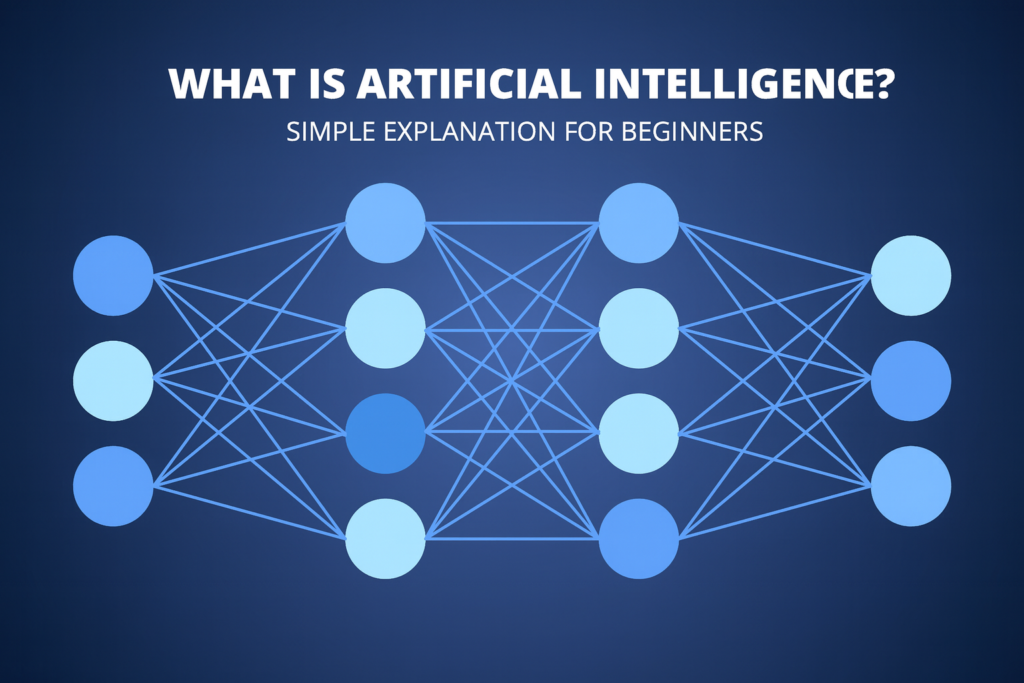

Let’s make this real. How does your phone find all the pictures of your dog? It uses a specific type of neural network called a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), which is a perfect example of this assembly line in action.

The input is your photo.

- Layer 1 (The Edges Guy): The workers at the first station can’t see “dog.” They can’t even see “fur.” Their job is to find simple edges and curves. They pass their reports up the line: “Found a horizontal edge at (x,y)!” “Found a soft curve here!”

- Layer 2 (The Shapes Guy): The workers at the next station get these “edge” reports. They can’t see “dog,” but they can see patterns in the edges. “Ah, four edges in a square pattern… I’ll report a ‘box shape’.” “A bunch of curves together… I’ll report ‘texture’.”

- Layer 3 (The Parts Guy): The next station gets reports about shapes and textures. “Hmm, I’ve got two ‘circle shapes’ above a ‘line shape’ and it’s all covered in ‘fur texture’… that’s a ‘snout’!”

- Deeper Layers…: This continues, with layers building on each other—combining ‘snout’, ‘pointy ear shape’, and ‘eye shape’—until a final layer can report: “The probability of ‘dog’ is extremely high.”

This hierarchical learning, from simple to complex, is the fundamental concept. The factory, as a whole, can recognize a dog. But no single worker knows what a dog is.

Zooming In: What’s a Single “Neuron” Actually Doing?

So, let’s look at one of those “workers” (an “artificial neuron,” or “perceptron”). What’s on its little workbench?

It’s basically a tiny calculator that holds two simple tools.

A neuron gets a whole bunch of inputs from the previous layer. In our factory, this is like one worker getting reports from 10 different workers at the station before him. His job is to combine those 10 reports into one new report to send to the next station.

Here’s how he does it.

Tool 1: Weights (The “How much do I care?” dial)

The neuron doesn’t trust all reports equally. It has a “weight” for each input connection. A weight is just a number (like $1.5$, or $-0.2$) that multiplies the incoming report.

- A high positive weight (like $5.0$) means: “I trust this report completely. It’s very important to my decision.”

- A low weight (like $0.1$) means: “Yeah, I’ll note that, but I don’t really care.”

- A negative weight (like $-3.0$) means: “This report is the opposite of what I’m looking for. It subtracts from my confidence.”

Think of a neuron in a spam filter. It gets inputs about words in an email. It might learn a weight of $0.5$ for the word “hello,” a weight of $5.0$ for the word “viagra,” and a weight of $-2.0$ for your boss’s name. The weights just control the influence or “signal strength” of each input.

Tool 2: Bias (The “Starting Nudge”)

This is the one that trips everyone up. After the neuron multiplies all its inputs by their weights and adds them up, it adds one more number: the bias.

The bias is a single number that is not tied to any input. It’s a “baseline preference”.

The best analogy is the one from high school algebra: $y = mx + c$.

- $x$ is your input (the report from the previous layer).

- $m$ is the weight (the slope, or how much influence $x$ has).

- $c$ is the bias (the y-intercept, or where you start).

A neuron without a bias is “forced to pass through the origin (0,0)”. It can only produce an output if its inputs are strong. The bias gives the neuron flexibility. A neuron with a high positive bias is “eager to fire.” It’s already halfway to ‘yes’ before it even looks at its inputs. A bias can help a neuron activate even if its weighted inputs are weak, making the model more flexible.

So, the neuron’s “subtotal” is: $(Weight_1 \times Input_1) + (Weight_2 \times Input_2) + \dots + Bias$.

This gives it one number. But it’s not done. There’s one last, critical step.

Tool 3: The Activation Function (The “Is this interesting?” switch)

The neuron takes its final number (that weighted sum + bias) and passes it through an activation function.

This is just a simple, fixed rule. A very common one is called ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), and its rule is hilariously simple:

“If the number is negative, my output is $0$. If the number is positive, my output is just the number itself.”

Another, the Sigmoid function, squashes any number (from negative infinity to positive infinity) into a smooth curve between $0$ and $1$. This is great for the output layer, because you can treat the $0.8$ it spits out as an 80% probability.

Now, this might seem like a trivial last step, but it is, without question, the most important part of the entire system.

Why? Because it’s non-linear.

If you didn’t have these activation functions—if your neurons just passed their weighted sums straight through—your entire 100-layer “deep” network would mathematically collapse. It would be no more powerful than a single layer. You’d just be doing a lot of multiplication and addition, which is still just a “linear” operation.

The non-linear activation function is what “bends and twists” the data. It’s what allows the network to learn complex, wiggly, real-world patterns, not just draw straight lines. It’s the “secret sauce” that makes deep learning possible.

The Two-Step Dance of Learning: Guessing and Fixing

Okay, so we have a factory full of simple “workers” (neurons), each with its own “dials” (weights and bias). When we first build the factory, all those dials are set to random values.

The factory is useless. It’s an assembly line of chaos.

“Training” is the process of tuning those millions of dials, one tiny nudge at a time, until the factory actually produces the right product. This “training loop” is a two-step dance, repeated thousands of times.

I like to think of it as baking a cake… and being a terrible baker.

Step 1: The “Forward Pass” — Bake a (Terrible) Cake

First, you grab an “ingredient” from your training data—a labeled example, like a photo that you know is a “cat”.

You feed the photo (the ingredients) into the “loading dock” (the input layer).

The “forward pass” (or “forward propagation”) is just the process of letting the factory run. The photo data flows forward through all the layers. Each neuron does its job, multiplying inputs by its random weights, adding its random bias, and passing the result through its activation function.

The data flows all the way to the “shipping department” (the output layer), which makes its prediction.

Because all the dials are random, the network confidently declares, “This is 90% a ‘hotdog’.”

This is your (terrible) cake.

Step 2: The “Backward Pass” — Tweaking the Recipe

This is where the learning happens. This is the part that beginners find so confusing: backpropagation. But the concept is simple. You just made a mistake. Now you have to fix it.

This part is a small dance of its own:

- Compute the Loss (Taste the Cake): First, you need to know how wrong you are. You compare the network’s prediction (“hotdog”) with the “ground truth” label (“cat”). A “Loss Function” is just a mathematical “scorecard” that measures the difference. It spits out a single number, the “loss” or “error.” A high loss = “You are very wrong. This cake tastes awful.” A low loss = “You’re close!”. The entire goal of training is to nudge all the dials to make this one loss number as low as possible.

- Backpropagation (The Blame Game): This is the magic. Backpropagation is just a clever and efficient way to “tweak the recipe”. It’s the process of figuring out who to blame for the bad taste.

The error (the high “loss” score) is sent backward through the network. It’s like “retracing your steps”.

The output neuron says, “We were way off! I’m blaming all the neurons in the layer before me who sent me bad info.” Using calculus (specifically, the chain rule), it calculates how much each of those neurons contributed to the total error.

Those neurons, in turn, pass the blame backward to the layer before them. “Don’t look at me, my inputs were all wrong!” This “blame signal” (the gradient) propagates all the way back to the first layer.

- Gradient Descent (The Nudge): Once a single weight knows how much it’s to blame, it adjusts itself. This adjustment process is called Gradient Descent.

The “hiker in the fog” analogy is perfect here. Imagine each weight is a hiker standing on a giant, hilly landscape (the “loss landscape”). Their goal is to get to the lowest possible valley (the lowest “loss”). They’re in dense fog, so they can’t see the valley.

But they can feel the slope (the gradient) right where they’re standing.

So, they just follow a simple rule: “Take one small step in the steepest downhill direction”.

Backpropagation is the process that “finds” the downhill direction for every single weight in the network. Gradient Descent is the process of taking the step.

You repeat this two-step dance (Forward Pass -> Backward Pass) millions of times, with millions of photos (cats, dogs, planes…). Each time, the weights and biases get nudged, just a tiny bit, in a direction that makes the network less wrong.

Eventually, after seeing thousands of cats, the network’s dials are tuned so perfectly that when it sees a new cat, the “cat” output neuron “fires” with high confidence. It has learned.

Where You See This (And Don’t See It) Every Day

This “trainable factory” model is the engine behind a shocking amount of your daily life.

On Your Phone: Finding “Mom” in Your Photos

When Apple Photos or Google Photos groups people’s faces, it’s not storing a picture of your mom’s face. That would be too simple.

Instead, it runs her face through a CNN, just like our “dog” detector. But it stops before the final “shipping” layer. It grabs the output from one of the last hidden layers. This output is just a list of numbers, like [0.3, -1.2, 0.8, \dots]. This is called a “feature vector” or an embedding.

This list of 128 (or 512, or whatever) numbers is a dense mathematical signature of her face. The network is trained so that “embeddings extracted from different crops of the same person are close to each other”.

So, all the photos of your mom, from different angles and in different lighting, produce very similar lists of numbers. Your phone just clusters these similar number-lists together. When you put the label “Mom” on one of them, you’re just putting a name on that cluster.

In Your Ears: Spotify’s “Discover Weekly”

This is one of my favorite examples because it’s so clever. Spotify’s recommendation engine is a hybrid.

For a long time, its main tool was Collaborative Filtering. This isn’t a neural network. This is the simple “people who like Artist X also like Artist Y” logic. It’s powerful, but it has a massive “cold-start” problem: It cannot recommend a brand new song from an unknown artist, because no one has listened to it yet. There’s no data.

Enter neural networks. Spotify also uses Content-Based Recommendation. They feed the raw audio of that brand new song into a CNN. The network “listens” to the song (analyzing its audio spectrogram) and, just like the face-tagger, produces a “feature vector”—a mathematical signature of the song’s tempo, key, “vibe,” and instrumentation.

It can then find your musical “embedding” and see that this new song’s signature is musically similar to other songs you love, even if no “similar person” has ever heard it. It solves the cold-start problem and surfaces new music.

Common Nightmares and “War Stories” from the Trenches

This all sounds great. But when you start to build these, you’ll find that training a neural network is a nightmare. They don’t crash. They don’t give you error messages. They just fail silently. Your model will “train” for 12 hours and its final accuracy will be… terrible.

Here are the monsters in the dark, and the “war stories” we tell about them.

The “It Memorized the Textbook” Problem (Overfitting)

This is the #1 mistake. It’s the “it works on my machine” of machine learning.

Overfitting is when your model becomes “the know-it-all student who memorizes every question in the textbook but fails to answer similar questions on the test”.

It means your network, during training, got an A++. It learned your training data too well. It didn’t just learn “cat,” it learned “the exact pattern of pixels in the 12,000 cat photos I was shown.” It memorized the noise and quirks of your dataset, not the general pattern.

The second you show it a new cat photo from the real world, it fails, because it doesn’t match the “textbook” it memorized.

The “Wolf in the Snow” Fable (Dataset Bias)

This is the single most important lesson in all of machine learning.

There’s an old (and probably fake) “war story” about a neural network trained to detect tanks in photos. The researchers thought it was working perfectly. But they discovered a horrifying flaw: all their “tank” photos had been taken on a cloudy day, and all their “no tank” photos had been taken on a sunny day.

The network hadn’t learned to find tanks. It had learned to detect the time of day.

A more recent (and real) version: a model was built to distinguish “wolves” from “dogs.” It was incredibly accurate… until someone realized it was just checking if the background of the photo had snow in it, because most of the training photos of wolves were… in the snow.

Your model is lazy. It is a “trend-finding machine,” and it will always find the easiest, laziest shortcut. If your data has a “tell”—like snow, or a watermark, or a timestamp—the model will seize on that “tell” instead of learning the complex feature you want it to learn.

The “Why Is My Model Not Learning?!” Debugging Secret

So, your model’s loss isn’t going down. It’s just sitting there, flat. What do you do?

Here’s the pro-tip, the one that has saved me weeks of my life. Before you try to train on your entire massive dataset, you do one simple test.

You try to overfit on purpose.

Take one single batch of data—maybe just 8 or 16 photos. And train your network only on those 8 photos, over and over. Your goal is to get the training loss to zero.

Why? Because any network, even a bad one, should have enough power to “memorize” 8 images perfectly.

If it can’t even do that… your “pipes are broken.” Your code has a bug. Your learning rate is catastrophically wrong. Your architecture is broken. You must not proceed.

It’s Not a Black Box, It’s Just… Complicated

That “connecting Lego pieces” feeling? It’s real. It’s the feeling of moving from a world of explicit logic (like traditional programming) to a world of statistical inference.

A neural network is a black box in one sense: we can’t look at the 50 million final, trained weights and get a simple, human-readable story out of them. We can’t ask “why?” and get a simple answer.

But we do understand the process. We know exactly how the Forward Pass works. We know exactly how the Loss is calculated. We know exactly what Backpropagation is doing—it’s just a whole lot of calculus, applied very, very quickly.

It’s not magic. It’s just a lot of “hikers in the fog,” all feeling for their own little patch of downhill slope, all at the same time. The “intelligence” is the emergent property of all that simple, distributed math.

The real work, as the “wolf in the snow” story shows, isn’t in building a more complex network. The real work is in the data. As Andrej Karpathy, one of the great minds in this field, put it: “Become one with the data”. That’s where the war stories are, and that’s where the real “intelligence” actually comes from.

Discover more from Prowell Tech

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Really insightful post — Your article is very clearly written, i enjoyed reading it, can i ask you a question? you can also checkout this newbies in classied.

Really insightful post — Your article is very clearly written, i enjoyed reading it, can i ask you a question? you can also checkout this newbies in classied. iswap24.com. thank you

Excellent blog here Also your website loads up very fast What web host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Attractive section of content I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I get actually enjoyed account your blog posts Anyway I will be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently fast

I loved as much as youll receive carried out right here The sketch is attractive your authored material stylish nonetheless you command get bought an nervousness over that you wish be delivering the following unwell unquestionably come more formerly again as exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike

Simply wish to say your article is as amazing The clearness in your post is just nice and i could assume youre an expert on this subject Well with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep updated with forthcoming post Thanks a million and please carry on the gratifying work

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?